WHERE SHOULD FRICTION BE IN OUR ROPE RIGGING SYSTEMS?

Hello fellow arborist. I am not an engineer and I am not a technical writer. I am going to write on the level of most of us; because I am a tree guy, like most of you. I will write my articles from what I observe and what I have learned over the years by real work experience. I will not be researching numbers, angles, technical information and regurgitating it here in an attempt to seem brilliant and above most of the readers. In doing so, hopefully, reading what I write will get to the point, be interesting and understandable.

We need friction in lowering weight, so where should it be?

When climbers need to lower limbs or logs and the weight or force is more than a person can handle; friction is needed somewhere in the rigging line in order to control the decent. In the last 50 years or so in arboriculture, the common practice has been that friction is applied to the rope at the base of the tree to allow a person to handle large weights. This is usually done with either a lowering device or the old school way of doing wraps around the tree trunk.

This brings to mind a funny story someone recently told me. They said that at their tree service company, they use the Hobbs lowering devices. [which you may know is a serious, big and heavy tool] They told a friend (that also had a tree service) that he highly recommended the Hobbs lowering device. Consequently, that friend purchased a Hobbs LD. After the first week of use; the veteran Hobbs user calls up his friend and asked how does he like his new Hobbs? He answered that it is okay, but it takes them a VERY long time to haul it up to the top of the tree and is exhausting to do so.

I laughed when I heard it, but you know what? That guy had something right, whether he knew it or not. He was thinking of adding friction at the top of the tree.

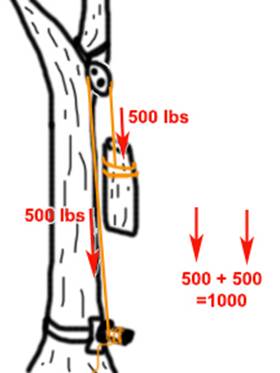

You see, if we have all of our friction at the bottom of the tree and we are using near-frictionless blocks and pulleys, we are multiplying the forces on the rigging points. For a simple example; hanging a 500 pound log off of a pulley up in the tree and to a lowering device at the base of the tree; the system doubles the force applied to that block, the sling and the rigging point in the tree. So at least 1000 pounds is applied to that rigging point when using a pulley/block and friction device at the base of the tree.

Then, apply the multiplication of a load falling some distance, such as negative rigging and the forces applied can be huge! Then add in a mistake such as a “no-run” and sudden stop and things get even crazier.

To deal with these forces, crews needed to have ground people with excellent lowering skills that could let the tree material “run” towards the ground and slowly decelerate it.

If the ground person does NOT let a heavy log or limb run and slowly decelerate, the climber can easily get bounced around and hurt. Or the sling on the block could fail, or the rope could fail, or even worse things like the tree failing.

I fortunately have had excellent ground people over the many years and they have mastered the art of letting material run, then slowing it to a stop where needed. However, I have also been through the jarring motions of too many wraps or the fear of an inexperienced person freezing up and holding tight to the rigging rope.

I know a lot of climbers that have completely given up on lowering large logs and limbs; it’s not worth the risk to them, they have had too many bad experiences. Many climbers would rather play it safe by cutting pieces small. This often is not efficient and in some cases light weights can be close to impossible with large diameter trees. I have friends that take things small and claim that they are very efficient and fast at it and I do believe them. In my area, most of the wood gets hauled away and not left on site as firewood rounds. I would rather haul away logs and get paid for those logs rather than move around numerous firewood rounds. I also would rather see a 40 foot long limb go through the chipper in one piece instead of that limb in 6 pieces. But that’s just me and my area of work; let’s get back to the subject.

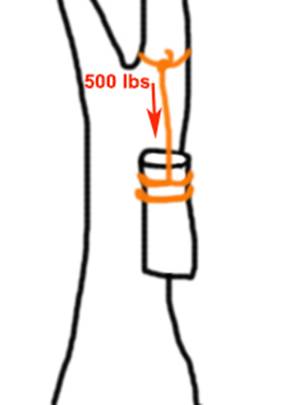

Now, instead of a block in the tree and a lowering device at the base, let’s go to the top for the example. IF you take a single leg of rope and tie a 500 lb. log and hang it from a tree, you are applying 500 lbs. to the tie point. There is only one leg of rope pulling down on the point that you tied the log to.

So, you might be thinking, well, let’s apply friction to the top of the tree. This is okay and can be great when used correctly. People have used porta-wraps, figure eights and the tree itself when they understood this concept. It definitely lessens the force put on the rigging point. However, there is often very little rope length being used in the system between the friction device and the load. Short rope length can be a VERY bad thing. Long lengths of proper rigging ropes have stretch and can help absorb shocks and jarring. A person could also use natural crotches and wraps in the top of the tree. This is a unique skill and requires a lot of experience. Varying diameters and bark types can make it hard to judge from one tree to the next. If a person gets it wrong and the load does not run, they are shock loading a short section of rigging rope. If this keeps re-occurring, they are fatiguing the end of that rope over and over again until one day it breaks.

Smoother Lowering with the Magic of Friction

So, how about something in between? How about a lowering device at the base and rigging point hardware that is not blocks/pulleys, but instead adds some friction and allows the entire rope length to be used?

Now, a block with clutch plates would be cool and likely work well if there was such a thing; where you could dial in the amount of braking on the sheave of the block. But it would be expensive and blocks are already expensive.

So, what would work with some friction, be simple, and not so expensive?

Well, the X-Rigging Rings (XRRs) were introduced to the arborist industry in 2012 by Xtreme Arborist Supply and they do just that. These are a low friction ring that the rigging rope runs through. When you are adding friction to a rigging point, you are not multiplying the force on the rigging point as much as you were when using a near-frictionless block. When you have friction at a rigging point, you are lessening the force on one leg of the rope that is pulling on that rigging point.

Photo courtesy of Xtreme Arborist Supply Inc.

Photo courtesy of Xtreme Arborist Supply Inc.

Since there is friction at the rigging points (on the rings) you are not multiplying the force as much as when using a block; if someone makes a mistake (as in not giving as much “run” as requested); the mistakes are not multiplied as much as it was with blocks. I find everything is less violent. Things go smoother. The ground person does not have to be so perfect. (Although, this smoothness and less violence has been tempting me to go larger and larger to find the edge of uncomfortable again.) When we use several rings in a rigging system (such as a few redirects and then also rings as the terminal rigging point); on weights that we would normally have three required wraps on a Hobbs or GRCS, we now use only one wrap. I have been using this type of ring since 2011.

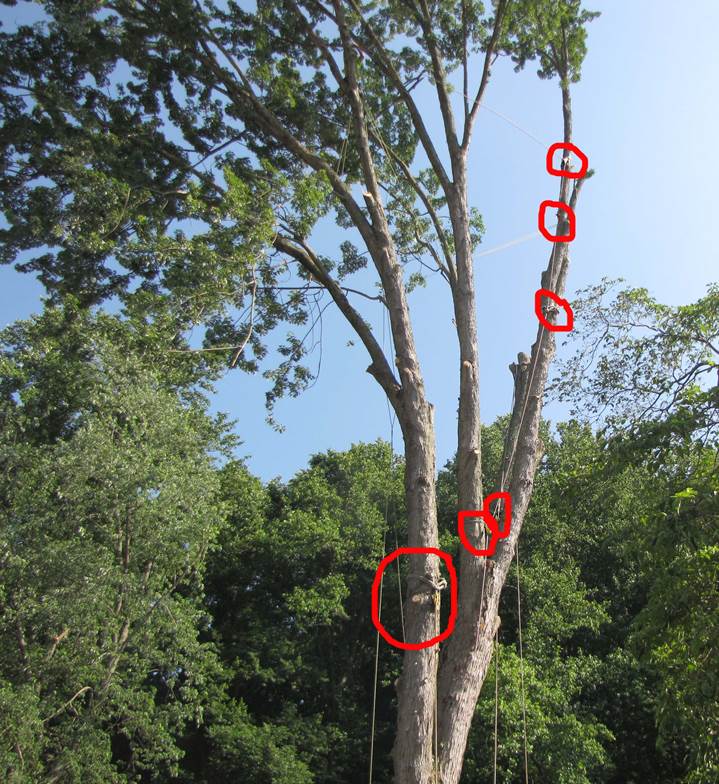

Even the large red oak logs pictured in this article were lowered smoothly and decelerated to a stop about 6 feet from the ground. The redirects and rigging points were all X-Rigging Rings.

Photo courtesy of Arbor-X Inc.

My ride was very calm and stress free. On the largest logs, two 1 inch diameter rigging lines were used. One rigging line ran from a Hobbs device, the other from the aluminum bollard on the GRCS(Good Rigging Control System), through a set of extra-large X-Rigging Rings (nicknamed the “beast rings”) -that pulled the lines away from the log slap zone on the trunk. The terminal rigging points were two more sets of the extra-large “beast” rings in a double ring configuration.

On the numerous heavy logs, there was no smoking/glazing of rope at any of the rings or the Hobbs. From lowering the heaviest log (3,760 lbs./1706 kg. ) there was a short ribbon of melted rope on the GRCS bollard; this was the hottest friction item in the system due to the bollard being somewhat thin aluminum compared to the aluminum of the Hobbs. The hard-coat anodizing of the rings reduces friction heat on the rings; the “beast” 38×28 rings have a serious amount of aluminum to dissipate heat as well.

Sharing Loads

Smart rigging arborists like to use the trees structure to make the tree and system stronger. Rigging redirects are very safe and effective, but most climbers do not understand how huge the benefit is. If heavy weights are going to be lowered, or if the final/terminal rigging point is out on a somewhat questionable limb; rigging redirects should be used so that the rigging point in the tree is not broken. Redirects use a tree’s shape to reduce forces on rigging points. The final rigging point can even lift upward and improve as more weight is put on the end of the rigging rope if redirects are used.

You need a lot of rigging hardware if you are going to have multiple re-directs. Multiple devices can add up to be expensive if each item is expensive. In the past when I used blocks for lowering on large spreading tree removals; I could have up to 5 or 6 blocks in a tree. Blocks that ranged from $220 to $600 each. I could have $1700 of blocks in a tree and that doesn’t include the cost of slings.

Photo from the past, showing multiple arborist blocks in a spreading silver maple removal.

High costs prevent people from purchasing hardware for redirects. Redirects make things safer, but if redirects are costly in hardware, a person might tend to now own that hardware.

An inexpensive low-friction devise is the way of the future when it comes to lowering.

A quote from Lawrence Schultz, New York, “the strength to weight ratio of the X-Rigging Ring slings is unbeatable. They make force distribution a breeze all while enabling you to retain maximum rope strength, allowing for the strongest rigging architecture possible. My production is way up and my worries are way down.”

When Glenn Riggs, a tree worker in Pennsylvania, got his first X-Rigging Rings, he contacted me and said he really liked them and shared what he had been using for many years. It was a clevis shackle that had another clevis U shape welded to it to increase the width. It was an ingenious homemade tool and it was exciting to find something achieving the similar low cost and adding friction.

Clevis donated by Glenn Riggs, PA.

He still uses both the homemade clevis devices and the XRRs. “Doubled up 5/8inch steel shackles have been a part of my tree rigging for two decades. My number one choice over cheap small pulleys for limb rigging. The X rings have taken over as my number one in the last two years. Small, light, super strong. My son Jake has one always on his saddle for quick lowering…”

When European arborists saw the XRRs, some informed me that years ago, before blocks, there was this thing they called a strop in Europe. I was told they were approximately 24mm three strand nylon slings with a spliced eye and metal thimble in the eye for lowering. The metal thimble looked galvanized. They said the tight bend radius and friction of the strop often caused ropes to snap.

Strop picture, courtesy of John Lawrence, United Kingdom.

In contrast, the X-Rigging Rings are hard-coat anodized machined aluminum, the anodized surface makes it slick and hard as tool steel. The ring gets its strength from its thickness and more importantly, the sling cordage that fills the groove around the ring. The hard-coat anodize outer layer is much more effective at keeping temperatures down as compared to steel friction products.

If you have a rigging system of say a large stainless steel Porta-Wrap and X-Rigging Ring slings and you intentionally do a long fast run to abuse and attempt to smoke the rope….. You will smoke and glaze the rope on the porta-wrap way before the rings ever will. The rings stay surprisingly cool compared to other friction components in your system.

In the past I used steel carabineers with loop runners on my speedlines. Those steel carabineers can heat up and can burn a ground person’s fingers while disconnecting them from the speedline. That’s too hot! I have also bent them and had gates open up in brush. I still use the steel carabineers and loop runners on my lightweight speedlines. But for heavy speedlines and vertical speedlines the XRRs come out to play. They have less friction, are wider and cooler running than steel or aluminum carabineers that are not hard-coat anodized.

When lowering small to mid-sized limbs, users find that on limbs that would normally be too heavy to handle using a pulley with no lowering device; they can now handle that limb weight with just rings alone. NO lowering device at the base of the tree. We typically use a ring or two at the top of the tree and a ring as a basal redirect on the average white pine or spruce removal. That is all the friction needed to lower most spruce and pine limbs. No need for wraps, no need to ever take it out of the ring.

Top of the Tree Friction Tools

With the industry slowly realizing that friction is important up IN the tree; I suspect other tools designed to do this will be coming out in the future.

A top-of-the-tree friction device that was lightweight and did not apply too much friction would be a very useful tool.

This belay spool might be such a product for light weights:

Courtesy of BMS Rescue Equipment

I have heard that some people like this spool for top of the tree friction. Its SWL(safe working load) is stated as 600lbs. It was not designed for the arborist industry, but has been adopted by some. It appears that you attach it with a carabineer. If so, the carabineer with it’s narrow diameter on the sling would likely be the weak point. But if following the SWL, this should be fine.

Some existing tools a climber might use are likely already in their tool kit; figure eights and Porta-Wraps.

Figure Eights tend to spin the rope under load, causing weird twists and knots, they also apply too much friction in my opinion.

Porta-Wrap type of devices with no side plates can lose a wrap with swinging or negative rigging loads.

The Belay Spool (pictured above) has two side plates that come together at the carabineer or shackle attachment point. I have not used this device, but I’ve heard good reviews for light to medium weights. It uses small diameter rope and is NOT designed for tree work. Most tools get abused by tree workers, so I prefer things that can handle huge weights and abuse but keep the users safe even (if they make mistakes).

One such product is coming out soon. The X-Rigging THT (Three Hole Thimble).

Patent Pending THT from Xtreme Arborist Supply.

On medium to large weights, problems such as too many wraps is not possible with the THT. Also, wraps coming off is not possible with the THT. The rope can never come off. The climber adds friction with the THT by weaving the rope through the holes. Using all three holes is never going to add too much friction (for any significant weight) and cause things to lock up/shock load (like too many wraps on a porta wrap). Therefore, it will not stress the short section of rigging rope that I touched on earlier. If only the slightest amount of friction is desired, two holes can be used instead; or even just a single hole like the XRRs. The groove around the device is the sling attachment (similar to the rings) and actually gives more strength to the tool. There are no moving parts and it is constructed of solid aluminum. The aluminum is hard coat anodize on the surface. There is no circular wrapping like most friction devices. Due to the straight line of friction, the rope does not get kinks or hockels like circular wrapped devices.

It can be used on control-lines as an unmanned friction device to slow down the swing of a load. When lowering medium sized material with a THT a groundperson can tend the rigging rope while the climber makes the cut as usual. Then the ground-person lowers the load. The climber takes over on the rigging line because the THT is creating enough friction and the ground-person is now free to work at laying the load down. So, not only are you putting less force on your rigging point when using a friction tool at the top of the tree, you often can work with two crew members almost as easily as if you were working with three. The THT can be used on huge weights in conjunction with a basal lowering device to give friction at the rigging point and greatly diminish the loads on the rigging point. I particularly use it when compromised limbs are my only rigging choices available. I feel better knowing that less force is placed on the limb verses if I was using a block and lowering device at the base of the tree.

The THT also creates MORE fiction as it inverts during the transition in negative rigging.

THT prototype in negative rigging. THT using two holes on limb lowering. Photo by Xtreme Arborist Supply Inc.

These are exciting times in tree rigging – don’t be left behind.

J. David Driver is owner/president of Arbor-X Inc. A Tree Service in Bel Air, MD,

a TCIA member company since the year 2000.

Also president of Xtreme Arborist Supply Inc.

Treasurer of the Maryland Arborist Association.

ISA Certified Arborist and Maryland Licensed Tree Expert

Check out this video that demonstrates these concepts: